How Global Graft Networks and Media Warfare Sustain Autocracy

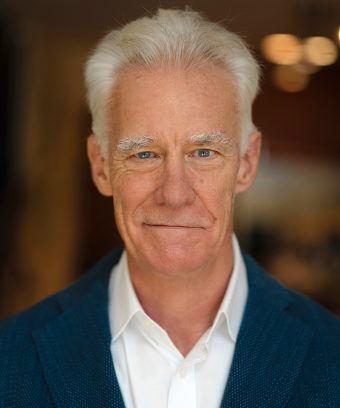

In this review of Anne Applebaum’s latest book, Autocracy, Inc., IGCC research director for global governance Stephan Haggard examines how autocrats weaponize corruption, international dealmaking, and misinformation to cling onto power and asks what policymakers in the democratic world can do about it.

In Autocracy, Inc., the journalist and historian Anne Applebaum reports on the fate of a steel plant in Warren, Ohio. A series of explosions at the plant beginning in 2010 not only had horrible human consequences, they finally lifted the lid on a consistent pattern of safety violations. In 2016, the plant closed with 200 workers losing their jobs.

This was not a tale of trade competition or the obsolescence of a technologically challenged facility. The plant was owned by a Ukrainian oligarch who—in that country’s more authoritarian past—used it as a vehicle to defraud a retail bank in Ukraine by laundering money. The story highlights a number of key themes in Applebaum’s book: the pervasive role of corruption in authoritarian regimes, the way in which such corruption sustains autocratic rule at home, and the ability of insiders within these systems to exploit global loopholes to internationalize kleptocracy.

A New Style of Authoritarianism

Applebaum has long been preoccupied with the origins and implications of authoritarian rule. This interest traces to her personal engagement with Eastern Europe and award-winning accounts of the imposition of Stalinist rule in Eastern Europe, the Soviet gulag, and the Ukrainian famine of the early 1930s. In 2020, she joined the chorus bemoaning what she called the twilight of democracy. She also provided insight into her personal political journey from center-right anti-communism to growing fear that the American right was becoming openly anti-democratic. Her new entry into the debate on authoritarian rule, Autocracy, Inc., shows the centrality of corruption to the new authoritarianism and the myriad ways that authoritarian regimes and their cronies cooperate to blunt democratic rule both at home and abroad.

“Unlike the fascist and communist leaders of the past,” Applebaum writes, “who had party machines behind them and did not showcase their greed, the leaders of Autocracy, Inc. often maintain opulent residences and structure much of their collaboration as for-profit ventures. Their bonds with one another, and with their friends in the democratic world, are cemented not through ideals but through deals—deals designed to take the edge off sanctions, to exchange surveillance technology, to help one another get rich.” As Christina Cottiero and I have argued, this playbook increasingly extends to the ways in which autocratic coalitions use international organizations.

Useful Idiots

A recurrent theme in Applebaum’s book is Western complicity in policies that are ultimately inimical to the common interests of democracies. She recounts the history of German Ostpolitik, which rested on the belief that democratic change in the Soviet bloc could be encouraged through economic cooperation. This cooperation included the pipeline deals that inadvertently enhanced Russian leverage over the European Union. Rather than weakening authoritarian rule, those deals were supported by self-interested politicians and private firms in the West who stood to gain from the capital flight orchestrated by the post-Cold War Russian elite. In good journalistic fashion, she traces the tentacles of this dealmaking to show how financial facilitators fuel kleptocracy in the offshore financial netherworld of shell companies and tax havens.

A related theme is how autocracies collaborate with one another to avoid sanctions through what Matthew Page and Jodi Vittori call “bridging jurisdictions” in their important report on kleptocrats’ collaboration. The bedfellows are odd but not surprising: Iran cooperating with Venezuela, China supporting the likes of Mugabe in Zimbabwe, Turkey and Central Asian states enabling Russia’s sanctions evasion by serving as middlemen. Applebaum picks up on the theme of regional bodies like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization performing similar functions and devotes a full chapter to what she calls “smearing the democrats”—propagating storylines about democratic dysfunction, with the transparent purpose of diverting attention from autocracies’ own disabilities.

Flooding the Information Zone

A central theme of the book is the increasingly coordinated effort to control the political narrative through systematic information—and disinformation—campaigns. While the United States wrings its hands over how to balance the costs and benefits of free speech, a loose autocratic alliance is pumping money into media that really are fake news. At the same time, they are providing the technologies that facilitate digital surveillance. Russia and China are both investing heavily to shape political narratives, for example in Africa, in ways that do long-term damage to American interests.

Appelbaum tells the story of a shadowy website called Pressenza that was founded in Milan and relocated to Ecuador in 2014. Pressenza is in fact a wholly owned Russian operation publishing in eight languages and propagating narratives such as the debunked Ukrainian bioweapons labs story. Both official state media and private satellite companies and content providers are capable of flooding smaller media markets where they can package tendentious content on the cheap. StarTimes, a semi-private China-linked satellite company with 13 million subscribers across 30 African countries, provides Chinese entertainment which—like a myriad of TikTok posts—carries positive messaging about the Beijing model.

What to Do About It

Perhaps the most enlightening chapter of Applebaum’s book is its conclusion, in which she considers the policy implications of her work. The challenge is increasingly daunting, precisely because we do not face a clearly defined adversary, but rather a shape-shifting set of networks that operate not through alliances or blocs but informally. Some policy recommendations are obvious, such as challenging disinformation through both government efforts such as the State Department’s Global Engagement Center, and by supporting non-governmental organizations such as those in Taiwan that have outed Chinese disinformation campaigns.

One of her most important policy recommendations, though, is to follow the money. The approach of the current generation of autocrats to wealth is a theme American political scientists have been slow to pick up on, perhaps because of their focus on political rather than economic affairs. It is typically central to those in the affected countries, however, and scholars such as the Hungarian Bálint Magyar’s Mafia State have detailed the model. Applebaum argues that more effort needs to be devoted to ending transnational kleptocracy by collaborating with democratic allies to clamp down on the financial facilitators—from London to Delaware—who facilitate the offshore financial sector.

The election of Donald Trump does not improve the likelihood that Applebaum’s agenda will gain traction. During the recent fight over the debt ceiling, the U.S. House of Representatives managed to kill all future funding for the Global Engagement Center. That lack of leadership from the government will make it more important that private foundations fund ground-level initiatives that will increase democratic resilience, from strengthening legal professions to the civil society groups that can push back against autocratic narratives.

Stephan Haggard is distinguished research professor at the UC San Diego School of Global Policy and Strategy and research director for democracy and global governance at IGCC.

Thumbnail credit: Wikimedia Commons

Global Policy At A Glance

Global Policy At A Glance is IGCC’s blog, which brings research from our network of scholars to engaged audiences outside of academia.

Read More