Trump’s Trade War: A Primer

As President Trump’s tariff strategy becomes clearer, David Lake, distinguished professor of the graduate division at UC San Diego and senior fellow at IGCC, takes a deep dive into the history of U.S. trade policy to understand why the country is making such a sharp break with the past. Lake concludes by asking whether this strategy will ultimately help American workers—or simply harm U.S. consumers.

The full essay is available below, or download the PDF here:

DownloadPresident Donald Trump fought a trade war with China in his first term and promised during his 2024 presidential campaign to fix America’s broken trade system. For decades, Trump claims, other countries have “ripped off” the United States in unfair trade deals, resulting in large trade deficits. But for the first six months of his second term, what “fixing” the trade system meant remained unclear. Tariffs were threatened, then imposed, suspended, reimposed, postponed, and finally enacted in some cases but not others. “Liberation Day” on April 2 came and went without any real change.

Only in early August 2025 has the president’s trade policy been clarified—and it is unlike any other in U.S. history. Its closest cousin is the mercantilist policies that flourished in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries, during which countries tried to balance trade flows while hoarding gold, ensuring that global trade was repressed.

Whether Trump’s new policy will work remains an open question. It defies economic logic, at least some of which, starting with Adam Smith, was explicitly developed in opposition to mercantilism.

U.S. Trade Policy History

There have been two major eras of U.S. trade policy. If Trump’s approach is sustained, it will begin a third.

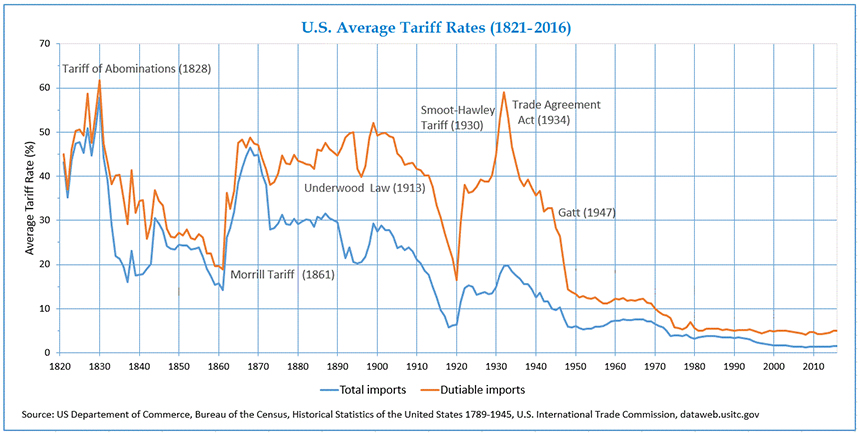

Congressional Protectionism (1787–1934): The Constitution assigns the power to regulate trade and set tariffs to Congress, which exercised its rights vigorously for over 150 years. Tariff rates varied over time, as shown in Figure 1. Prior to the Civil War, when votes were evenly split between the free trade South and protectionist North, tariffs were mostly used to raise revenue. After Northern victory in the Civil War, protectionism dominated. Throughout, the process and form which tariffs took remained relatively constant. The House Ways and Means Committee would hear petitions from producers and draw up a proposed tariff schedule; a flurry of amendments would be added from the floor by representatives who believed their firms and industries had not gotten the protection they deserved; the legislation would be passed and sent to the Senate, where the process would repeat; and the president would sign the completed bill. Logrolling was common, and indeed, expected: representatives would vote on protection for others in exchange for support for their own proposed duties. The overall effect was to increase tariffs beyond levels that any one person, firm, or legislator might think desirable.

Throughout this time, tariffs were set by product, and often finely graded by the level of “work” or stage of manufacture. For example, tariffs on textiles typically increased with the number of threads per inch. Equally, tariffs on raw materials and other inputs into the manufacturing process were duty free or taxed at much lower rates than finished products. The tariff schedule was set in an almost entirely inward-looking fashion. The needs of import-competing sectors were given priority. The notion of using reductions in U.S. duties to open foreign markets for American goods did not arise until the McKinley Tariff of 1890—and then only in limited form as a way of stimulating manufacturing exports to Latin America.

This system broke only during the Great Depression with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930, which continues to live in infamy. The U.S. and global economy never fully recovered from World War I. In particular, U.S. agriculture, which had expanded to meet demand during the war, was in crisis throughout the 1920s. Surpluses caused prices to fall, farmers who had borrowed heavily during the war to increase capacity went bankrupt, and droughts pushed farmers to demand government support, which under the terms of the day meant protection from foreign competitors even though the United States was a net exporter of farm products. Smoot-Hawley began as a limited revision of the tariff for agriculture, but in response to the Depression became a free-for-all, with nearly every industry demanding greater protection. The final bill was an orgy of logrolling and produced among the highest duties in U.S. history.

Smoot-Hawley set off a classic trade war of reciprocal increases in tariffs. Trade partners near and far raised tariffs in response. World trade plummeted by two thirds as national markets closed, exacerbating the effects of the Depression.

Presidential Liberalization (1934-2018): Congress responded to Smoot-Hawley and its ensuing trade war by passing the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (RTAA) in 1934. The RTAA delegated authority to the president to negotiate reciprocal reductions in tariff rates of up to 50 percent from Smoot-Hawley levels. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt moved swiftly to negotiate agreements with more than 16 countries. After the war, with European industry devastated and U.S. manufacturing essentially unrivaled, this same authority led the United States to create the General Agreements on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Over eight rounds of negotiations, the GATT dramatically lowered tariffs for nearly all industrialized countries, especially the United States and Western Europe. In 1947, before the first round, average tariff rates for 23 member countries were approximately 22 to 40 percent (the latter is the more commonly cited figure). By 1994, at the end of the Uruguay Round, average tariffs for 123 members were roughly 4 percent. Subsequent rounds of the GATT proved less efficacious as members moved to negotiate with developing countries and over nontariff barriers to trade. The GATT was reconvened as the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995, where the primary innovation was a more elaborate and binding dispute resolution procedure.

The GATT operated by the principal-supplier rule. When two or more countries wanted to negotiate tariff reductions on a particular product, the right to bargain for the best concessions was generally given to the principal supplier of that product to the country making the concession. In other words, if Country A imported most of its widgets from Country B, then B was the principal supplier of widgets to A; in a tariff negotiation round, B had the primary right to negotiate with A over widget tariffs. Once A and B struck a deal, the new lower tariff was extended to all GATT members under the most-favored-nation (MFN) principle. The effect of this practice was to rachet down nearly all tariffs over time.

Liberalization benefited consumers and exporters directly, dramatically increased global trade, raised per capita incomes, and brought more people out of poverty than ever before in human history.

Liberalization benefited consumers and exporters directly, dramatically increased global trade, raised per capita incomes, and brought more people out of poverty than ever before in human history. It also had severe distributional effects within countries. In the industrialized countries, owners of capital, highly skilled workers, and sectors that use capital and skilled labor intensively benefited enormously, while less-skilled workers and sectors that used labor intensively were harmed. These distributional effects were accelerated and magnified by technological change, which accounts for the vast majority (upwards of 86 percent) of manufacturing jobs lost in the United States in recent decades. Together, globalization and technological innovation have caused real wages for unskilled workers to stagnate or decline across the United States and Europe since 1972. The “shock” when China joined the WTO in 2001 further harmed less-skilled workers by effectively increasing the world’s labor supply by one third overnight, causing massive shifts in trade patterns and comparative advantage.

In the early stages of liberalization, attempts were made to cushion the effects of increased trade on workers through various social welfare programs, including Social Security and unemployment insurance, as well as more targeted efforts like trade adjustment assistance to retrain workers for other occupations. As the economy shifted towards comparatively advantaged capital-intensive sectors, income inequality grew, “coastal elites” prospered and became more politically influential, and under the Reagan-Thatcher revolution of the 1980s many social safety nets began to unravel. Under the so-called Washington Consensus around neoliberalism, and with the Democratic Party moving to the center under presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, neither of the major political parties in the United States responded effectively to working-class concerns. Therefore, it should not have been surprising that a nationalist, populist, and protectionist movement arose across the United States and Europe. Trump captured these disgruntled working-class voters in 2016 by articulating their grievances.

Trump’s New World

We can now see more clearly that Trump’s trade policy has several, though not necessarily consistent, aspirations, likely the result of competing factions within the administration. In rough order, Trump wants to balance flows of goods between the United States and each of its trading partners, meaning that U.S. exports of physical goods should equal U.S. imports on a bilateral basis. This is the clearest way in which his trade policy is mercantilist, but also appears to be his implicit indicator of whether trade is “fair.” This focus on physical goods ignores trade in services, in which the United States typically runs a surplus. Trump also wants tariffs to generate revenue for the government, perhaps to offset his continuing tax cuts. He wants to rebuild American manufacturing, especially in labor-intensive industries that “actually make things.” And finally, he wants to use the threat of tariffs to extract concessions on other issues, not least those that fit his larger personal grievances, such as the trial of former president Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil.

This was all unclear in his first term when he began a classic trade war with China—Trump imposed tariffs on Chinese goods, then China imposed tariffs on U.S. goods. Duties spiraled up, and trade spiraled down until the two sides called a ceasefire and preserved rates at their then-elevated levels. Throughout this period, it was ambiguous whether Trump was using tariffs to open the Chinese market to U.S. goods, services, and investment—delighting capital—or using tariffs to protect U.S. industry, pleasing workers. Trump also issued many exemptions, allowing firms that won his favor to import goods at the old rate of tariff—a fantastic way of distributing benefits to firms that supported his agenda. The opportunities for corruption were legion. The resulting coalition allowed both exporters and importers to get onboard, though they thought the train was going to different destinations.

Since retaking office in 2025, Trump launched a broader trade war encompassing the entire globe. Using both authority delegated by Congress to liberalize trade and expansive national security powers under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act—contested by the courts—the president is now reversing 250 years of trade practice and 75 years of trade liberalization.

For the first time, however, Trump is setting tariffs by country, not product. With few exceptions, he is also imposing tariffs on a flat rate, regardless of the level of “work” entailed. This is likely connected to his desire to balance bilateral trade, but both changes from historic practice are disrupting global supply chains and hurting U.S. manufacturers dependent on raw materials or intermediate inputs produced elsewhere. This combination has also led to some completely nonsensical tariffs, such as the often-cited example of 47 percent (later adjusted to 15 percent) tariffs on goods from Madagascar, which exports mostly vanilla that is not produced in the United States and, as a relatively poor country, imports few U.S. goods in return. The most-favored-nation principle central to the era of liberalization has now been abandoned; whether other countries will continue to employ it in their trade relations outside the United States is unknown.

What About the Trade War?

To date, Trump’s second term trade policies have not led to a classic trade war of reciprocally escalating tariffs. By threatening near prohibitive duties—in some cases, far above Smoot-Hawley rates—Trump has successfully extracted agreements with others on “merely” substantial increases in tariffs from current rates.

Prior to the recent agreement, the average tariff on goods from the European Union was less than 1 percent. In the face of a threatened rate of 50 percent, the EU settled for a 15 percent rate and declared victory. In some cases, Trump has extracted other concessions, including vague promises of increased investment in the United States. Trade “partners”—if that is still the right term—have not retaliated, at least so far. To the extent countries are responding, they are trying to diversify away from the U.S. market and negotiate deeper preferential trade agreements with non-U.S. partners. A large number of exemptions also appear to be in train, again allowing for firms to curry political favors with Trump.

Trump is exploiting U.S. market power to force others to absorb the costs of his tariffs.

In ways reminiscent of optimal tariff theory (OTT), Trump is exploiting U.S. market power to force others to absorb the costs of his tariffs. The main idea behind OTT is that very large countries can adopt tariffs that force exporters to lower prices of their goods sufficiently so that consumer losses are more than offset by tariff revenues, leaving the country as a whole better off. Economists have shown, however, that optimal tariffs are rare—if they exist at all—and apply only at the level of individual products, depending on the importing country’s share of the market and price elasticities (for an exception, see here). Unlike Trump’s current policy, optimal tariffs are extremely unlikely to exist for all goods exported by a country. While the lack of retaliation by others might accord with OTT, across-the-board duties by country make no economic sense according to current theory.

Interestingly, the only country exempt from Trump’s trade war—so far—is China. After threatening prohibitive tariffs of up to 145 percent, Trump imposed a 30 percent tariff on Chinese goods (a 10 percent universal reciprocal tariff plus a 20 percent fentanyl-related surcharge) and, as of now, has extended the deadline for negotiations to November 10, 2025, long past the date imposed on everyone else. China is the only country able and willing to impose painful retaliatory duties or other restrictions on the United States. Europe might have sufficient market power, but it chose to capitulate rather than fight. President Xi Jinping has made it clear that he will meet fire with fire in any trade war, using the dependence of the United States on rare earths and China-based supply chains to impose high costs on the United States. How this pending trade war plays out has yet to be seen, but the potential for great harm on both sides remains. It is more than a bit ironic that the United States’ most worrisome economic competitor may well escape the punishing trade policies Trump has imposed on its ostensible friends.

Will it Work?

Trump’s new trade policy may mitigate bilateral trade imbalances and will raise revenue. The administration is already crowing about the $100 billion in tariff revenue collected in the second quarter of 2025. Whether tariff revenue will offset the consumer loses is doubtful. Equally, whether tariffs will foster a reindustrialization of the United States is an open question. Even if firms and industries “onshore” production that was previously carried out “offshore,” it is likely to be far more capital-intensive and automated than advocates appear to assume.

American workers may benefit at the margin from trade protection, but a return of manufacturing is unlikely to restore the “good” blue-collar jobs promised by the president or lead to a significant increase in real wages for less-educated workers.

American workers may benefit at the margin from trade protection, but a return of manufacturing is unlikely to restore the “good” blue-collar jobs promised by the president or lead to a significant increase in real wages for less-educated workers. Comparative advantage still matters, regardless of the height of the tariff barrier. U.S. industries will always try to replace scarce (and expensive) labor with relatively abundant (and therefore cheaper) capital and technology.

Consumers—that is, all Americans—will lose from higher prices. Tariffs not only raise prices on imports, but by reducing foreign competition they also allow higher-cost domestic producers to survive and even expand. Domestic producers will, of course, pass their higher costs onto consumers and may even take advantage of less competition to raise prices further.

In the end, everyone in one way or another loses from tariffs—trade war or not. Congress gave the president the power to negotiate lower tariffs for a reason.

David A. Lake is distinguished professor of the graduate division at the University of California, San Diego and a senior fellow at IGCC.

Thumbnail credit: Mondoweiss