What Is At Stake in Turkey’s Election?

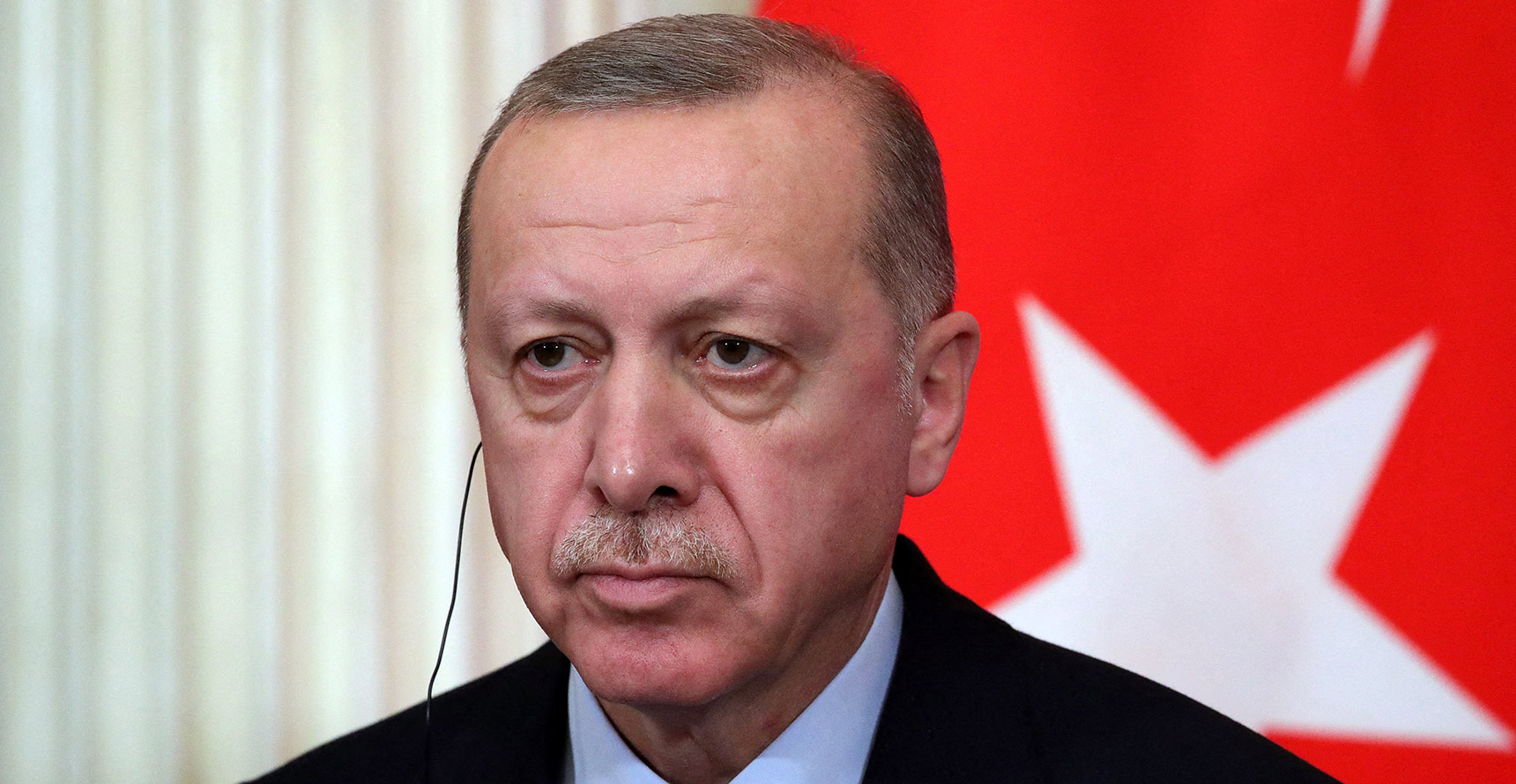

Democratic backsliding is on the rise globally, and Turkey has become a symbol of this worrying phenomenon. Sunday’s presidential and parliamentary elections were the first time in more than 20 years that Turkey’s populist President, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, faced an opposition that could defeat him in the elections. In this blog post, Furkan Benliogullari, a Ph.D. student at UC San Diego, weighs in on what is at stake for Turkey, and for efforts to defeat aspiring strongmen in Europe and beyond.

Turkey will have its presidential and parliamentary elections on May 14. For the first time in more than 20 years, Turkey’s populist President, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, faces an opposition that can defeat him in the elections. Under Erdoğan’s rule, Turkey’s democracy has steadily eroded and the country has gone further down the path of becoming an electoral autocracy. This election may be the final chance for Turkey to change course and reverse its move toward permanent autocracy with weak institutions and state capacity.

The elections will be consequential on several fronts:

Turkey’s Choice Between Autocracy and Democracy

Democratic backsliding is on the rise globally, and Turkey has become a symbol of this worrying phenomenon. Erdoğan became prime minister in 2002 and ruled the country with that title for 12 years with an increasingly authoritarian governing style. In 2014, he was elected president—a position in Turkey deemed by the constitution to require political neutrality. Erdoğan broke this convention and remained in control of his party, the Justice and Development Party (AKP). A failed coup attempt in 2016 facilitated constitutional amendments in 2017 that made Turkey a presidential rather than a parliamentary system—concentrating power in a strong executive branch—and legalized and completed the country’s authoritarian transformation.

Using emergency powers established after the 2016 coup attempt, Erdoğan solidified his rule by intensifying his crackdown on civil society, independent media, and political opposition. Although Turkey still holds elections, they are far from fair. The AKP recently changed the electoral laws to weaken the opposition, and Erdoğan has used the state’s full power to fuel his campaign.

What is at stake in this election is the democratic memory of Turkish people, who have been living under an autocratic regime for 10 years. Most polls give the main opposition alliance an edge in the first round and a potential run-off. An opposition victory could change the tide of authoritarianism in Turkey and Europe and serve as a recipe to defeat aspiring strongmen in Europe and beyond.

Turkey’s Failing Institutions and Diminishing State Capacity

In the process of democratic backsliding, populist leaders often coopt the state bureaucracy in an attempt to squash dissent and consolidate power. Erdoğan is no exception. Erdoğan and the AKP have filled the bureaucracy with loyal cadres over the last 20 years. Since their loyalty was the primary criterion for obtaining power, these bureaucrats proved to be incompetent in dealing with crises, such as the devastating earthquakes in southern Turkey in February 2023. Beyond the human tragedy, the World Bank estimates that physical damage in 11 provinces accounts for 16.4 percent of Turkey’s population and 9.4 percent of its economy, with direct losses estimated at $34.2 billion. The reconstruction needs could be double. Turkey lacks the resources to deal with this destruction.

The earthquakes also revealed the failure of local administrators to enforce the building regulations and of the government system more broadly to respond to the crisis. Since President Erdoğan operates within a now highly centralized presidential system (and in essence, has the final say over everything), the technical agencies and other critical bureaucracies—like the military—have been hamstrung in their response. Overall, the administrative capacity of the state has been woefully diminished.

If Erdoğan wins the election, Turkey is likely to continue its progress toward becoming an ever weaker state.

Turkish Economy in Ruins

The Turkish economy is dangerously close to collapse. The budget deficit has been increasing and Erdoğan forced the central bank to lower the interest rates to increase economic growth. However, low interest rates caused extraordinarily high inflation (they soared to more than 85 percent in October). The Turkish Lira lost 80 percent of its value in the last five years and low interest rates have caused foreign investors to leave Turkey and the lira.

Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, who is leading a coalition of six opposition parties, has vowed to reverse Erdoğan’s policies, tame inflation, and lure back foreign capital that has fled over the past decade if he unseats Erdoğan. Erdoğan meanwhile shows no sign of changing his disastrous economic policies.

Turkey’s Uniquely Unified Opposition

Over the course of Erdoğan’s rule, opposition parties—including nationalists, seculars, Kurdish parties, and other center-right parties—failed to become a viable alternative to Erdoğan. Today, for the first time in the last 21 years, Erdoğan is weak, and the opposition is unified. The economic crisis and spectacular destruction wrought by the earthquakes have laid bare the failures of Erdoğan’s regime. Meanwhile, the opposition parties have coalesced under Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu of the Republican People’s Party. His coalition includes a nationalist party, a liberal party, and three conservative center-right parties. Surprisingly, Kurds and socialists also support Kılıçdaroğlu. A coalition like this is exceptionally rare in Turkey or anywhere in the world. Their unity is driven by several shared goals: to defeat Erdoğan, re-establish parliamentary democracy; and re-orient Turkey westward.

But the coalition is fragile. The parties’ ideologies and agendas differ markedly, and if they fail to defeat Erdoğan now, it may be years before a coalition like this emerges again.

Turkey’s Foreign Policy Orientation

As Turkey has become more authoritarian, it has drifted away from Europe. Turkey’s loss of appetite for European Union membership was a sign of the changes taking place in Turkey’s foreign policy. Another was Turkey’s veto of Sweden’s and Finland’s accession to NATO. Turkey finally accepted Finland’s accession in March but continues to hold Sweden as a bargaining chip. Another indication of the drift is the fact that Turkey hasn’t fully implemented economic sanctions against Russia and continues to be a safe haven for sanctioned Russian oligarchs.

The opposition, by contrast, favors a re-alignment with the West and distancing Turkey from Russia and Iran. If Erdoğan wins, the gap between Turkey and the West may get wider and deeper.

What Happens if the Opposition Wins?

If Erdoğan wins, Turkey is likely to continue to consolidate as an electoral authoritarian state. But what happens if the opposition wins? Winning an election in Turkey does not always mean getting control of the state. Erdoğan and AKP filled public offices with loyalists, most of whom will continue their service, which means the opposition will have to work with them for some time. The opposition has a herculean task: to rebuild democracy, a flagging economy, and relations with the West. If they win, NATO and the West should support the new regime and help Turkey build back its earthquake-devastated regions, economy, state capacity, and democracy. If the expected miracle happens, a change in Turkey could encourage democratic oppositions in other states experiencing democratic backsliding in Europe and the world.

Furkan Y. BENLIOGULLARI is a PhD student at UC San Diego’s Department of Political Science. He studies the role of international law in interstate conflict.

Furkan Y. BENLIOGULLARI is a PhD student at UC San Diego’s Department of Political Science. He studies the role of international law in interstate conflict.

Photo credit: Mikhail Klimentyev

Global Policy At A Glance

Global Policy At A Glance is IGCC’s blog, which brings research from our network of scholars to engaged audiences outside of academia.

Read More