Beijing Calls for “Extraordinary Measures” to Boost Tech Self-Sufficiency

While Washington D.C. was marred in political deadlock over an unprecedented government shutdown, Xi Jinping introduced recommendations for the 15th Five-Year Plan, calling for “extraordinary measures” to secure China’s long-term science-technology autonomy. What should we make of this accelerated push toward self-sufficiency? What does it mean for China’s economic strategy and for global power dynamics?

The buzzword used by the party is “extraordinary measures” (采取超常规措施), which China will take to achieve “whole-supply-chain” (全链条) self-sufficiency in foundational industries and technologies, including semiconductors, in the next five years. This vague but important edict was issued as part of the Communist Party’s recommendations,” which are effectively instructions, for the country’s 15th Five-Year Plan, a developmental blueprint covering 2026 to 2030 that is slated for publication in March.

The party’s central committee issued the recommendations late last month, calling for “decisive breakthroughs” (决定性突破) that will lead to “high-level self-sufficiency” (高水平科技自立自强) in key technologies underlying six sectors: integrated circuits, machine tools, high-end precision instruments, basic software, advanced materials, and biomanufacturing. Together they form the core of an advanced industrial system, and some of them still require foreign inputs.

Although proclamations from China often include rhetorical flourishes, a People’s Daily editorial said the language used in the edict is “not merely a rhetorical upgrade in policy expression” but signals “profound mobilization” (深刻动员) to overcome intensifying containment from the West and win major-power competition by “seizing the commanding heights of scientific and technological innovation.” Another state commentary said these measures are not just urgent due to external pressure—but also because China, having raised its research and development (R&D) spending to roughly US$506 billion in 2024, is now positioned to “sprint toward the cutting-edge” (冲向科技制高点) rather than follow conventional paths.

One takeaway from the decision to deploy “extraordinary measures” is that Xi Jinping is likely not pleased with his nation’s pace of innovation. In 2020, announcements from the 20th Party Congress included an unprecedented “whole–of–nation” (举国体制) innovation system and a new “super commission” for science and technology led by the party. Massive investments followed in chip fabs, robotics factories, and science labs. And yet China still remains dependent on many key foreign technologies including advanced AI chips, jet engines, and semiconductor machinery.

The big question is, given China’s already-massive investments in science and technology, what more can be done?

At first glance, the “extraordinary” approach seems more of a continuation of what China has already been implementing: a centrally coordinated campaign that mobilizes and directs resources towards research projects, companies, and personnel to drive foundational research and accelerate innovation. On the industrial front, this includes massive state subsidies for scaling up these technologies for high volume manufacturing.

A more “extraordinary” version of this campaign may require more funding, higher political pressure, and harder targets. Simply put, the party is now saying ‘no more excuses, get it done, by any means possible.’

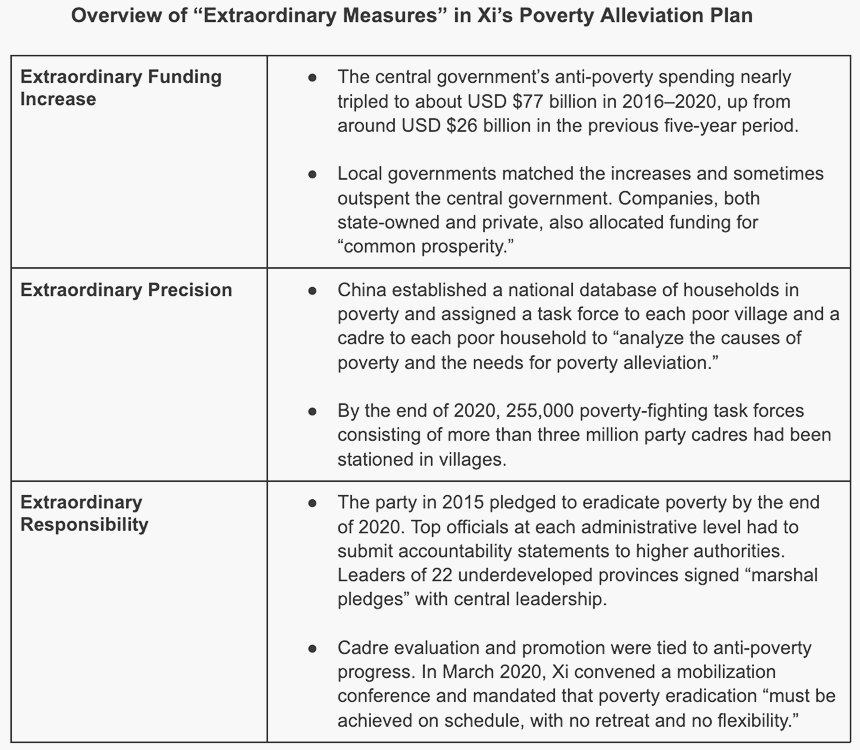

Historically Beijing has deployed “extraordinary measures” primarily for political aims. In these cases, sustained, high-pressure, top-down political mobilization (动员) campaigns are taken on to, for example, crack down on unrest in Xinjiang and root out grassroots corruption. A slightly more comparable precedent is Xi’s personal initiation of extraordinary measures to “resolutely win the war against poverty” (脱贫攻坚战) in China’s 13th Five-Year Plan. When the plan launched in 2015, Xi said,

“We must act with greater determination, clearer thinking, more precise measures, and extraordinary strength” (必须以更大的决心、更明确的思路、更精准的举措、超常规的力度).

It’s worth taking a closer look at Beijing’s methods for the anti-poverty campaign, because they may be dusted off and reused for technological self-sufficiency.

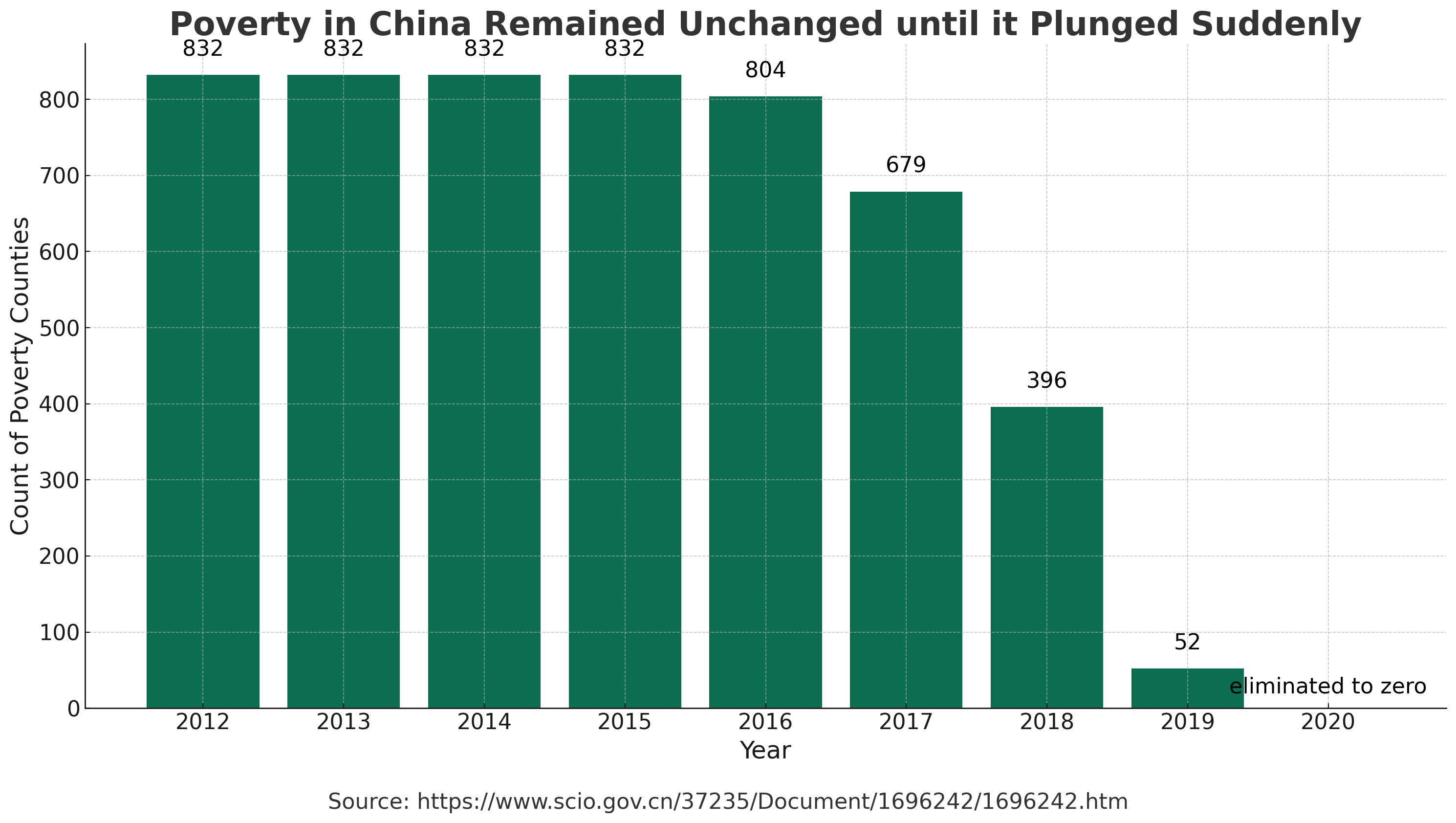

In 2021, Beijing declared complete victory over poverty. Its anti-poverty extraordinary measures worked, at least on paper. The official number of “poverty counties” miraculously collapsed just ahead of the deadline. However, the story is more complicated.

Tally of poverty counties according to official Chinese government statistics

A similar strategy could play out for science and technology innovation. Rather than earmarking funds for social welfare, the central government, local governments, and potentially even state-owned and private companies could begin allocating even more funds toward China’s national technology indigenization efforts. Research institutes and science and technology companies, many already generously funded, may be swimming in even more subsidies over the next five years.

A slew of new grandiose and ambitious national megaprojects and science labs will also likely be funded. China may similarly conduct a thorough audit of its industrial and technological supply chains, identify vulnerabilities, establish a national database, and dispatch task forces of party cadres to companies and research institutions to supervise and push for progress. A similar accountability system (责任制体系) may be designed for closing technological vulnerabilities, with company executives, researchers, and party officials assigned hard targets and required to sign accountability pledges. Their career prospects would be tied to technological progress.

It is unclear, however, if scientific and technological progress would respond similarly to such political campaign-style mass mobilization. To tackle intractable poverty, China relocated nearly ten million of its citizens to regions with supposedly better employment prospects. Whether doing so actually reduced poverty is unclear, but regardless, no such shortcut exists for research and development. Scientists already have to contend with increasing political interference in their work. Is more the answer?

Another takeaway from China’s “war” on poverty is that placing officials under extreme pressure to meet impossible goals incentivizes faulty data and exaggerated claims. The poverty alleviation campaign has been riddled with allegations that officials tampered with the statistics to create the appearance of success. Indeed, many poor Chinese villagers reportedly quickly relapsed back into poverty after the campaign was lifted.

In fact, then Chinese Premier Li Keqiang raised eyebrows when, in what was perceived as a rebuke to President Xi, he said poverty had not been alleviated since there were:

“still some 600 million people earning a medium or low income, or even less. Their monthly income is barely 1,000 yuan. It’s not even enough to rent a room in a medium Chinese city.” (还有 6 亿 人月收入只有 1000 元 左右,连在中等城市租房都不够).

To this day, whether or not China achieved victory against poverty is hotly debated.

In sum, Beijing will no doubt ultimately declare success in becoming wholly self-sufficient across the entire supply chain by 2030 through “extraordinary measures.” And China will see a genuine increase in its innovation power and self-sufficiency. However, if the past is precedent, it will be a messy process with mixed results—despite the party’s inevitable victory laps.

Jimmy Goodrich is an IGCC senior fellow. The views expressed by the author are his own and do not reflect those of any organization with which he is affiliated.

Thumbnail credit: Humphery, Shutterstock.com

Global Policy At A Glance

Global Policy At A Glance is IGCC’s blog, which brings research from our network of scholars to engaged audiences outside of academia.

Read More