Oceans of Ambition: The Rise of China’s Blue Science

When Xi Jinping said “the ocean has always been something I care about… It nurtures life, connects the world, and advances development”(“海洋,我历来是关心的…海洋孕育了生命、联通了世界、促进了发展.“), he was invoking both vision and story. A self-professed admirer of Jules Verne, Xi once remarked that “reading the science-fiction novels of Jules Verne filled my mind with endless imagination.” That spirit of imagination now surfaces in China’s ocean-science drive: fleets of submersibles, island observatories, and global monitoring networks that transform Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea into national policy reality. Guided by Xi’s “three deeps”—deep space, deep earth, and deep ocean (“深空、深地、深海”)—China’s marine research has become a 21st-century voyage of discovery, blending scientific curiosity with national purpose.

China has long pursued its ambition to become a “maritime power” (海洋强国), aiming for world-class capabilities in ocean research, resource exploration and development, maritime trade, and naval projection. It is now reaching for the frontier of deep-sea research, which is foundational to a host of disciplines, such as exploratory new energy sources, seismology, and undersea mineral and bio-resource development. It’s also central to submarine warfare, undersea infrastructure development and protection, territorial claims, and emerging undersea defense systems.

In fact, China is already a sea power, having grown its marine economy to over ¥9.91 trillion in 2023, accounting for 7.9 percent of national GDP. Its ocean-science efforts now span fleets of research vessels, deep-sea labs, and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), while internationally China is moving to lead major exploration projects previously dominated by the United States. This piece dives into China’s burgeoning ocean-science endeavors—how they’re structured, what they aim to achieve, and how they are rapidly challenging the long-standing ocean-science leadership of the United States.

Nearly Two Dozen New Ocean Science Labs and Universities Established

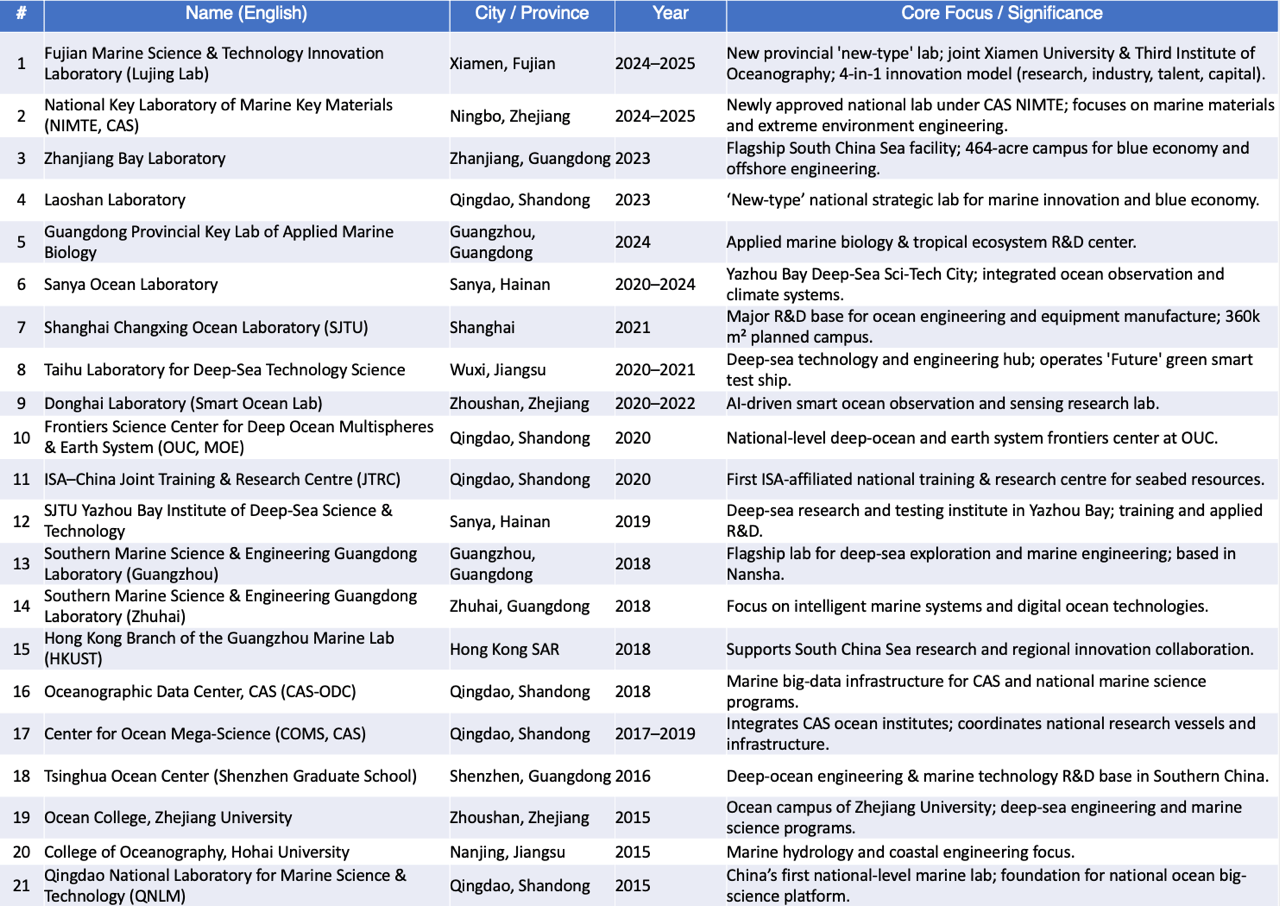

Nearly two dozen newly established government-run ocean science research labs are the main front of China’s efforts. Led by Chinese Academy of Sciences’s (CAS’s) Institute of Deep-Sea Science and Engineering and Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, a network of Chinese research labs has since sprung up—representing a central, provincial, and municipal government collaboration populated by more than 40 university programs.

Table 1: Over 20 Chinese ocean science related centers established since 2025

On the policy front, ocean science continues to remain a top priority for Xi. While former Chinese president Hu Jintao first introduced “maritime power” as a national strategic objective in 2012, Xi has made dozens of visits to ocean science or economy-related sites across China and has espoused frequently on the topic. For example, Xi said in 2018 that “to build a maritime power we must further care for the ocean, understand the ocean, master the ocean, and accelerate the pace of marine science & technology innovation” (“建设海洋强国,必须进一步关心海洋、认识海洋、经略海洋,加快海洋科技创新步伐”).

Ocean science is almost undoubtedly a top priority for China’s newly established Central Science & Technology Commission, and it now oversees a number of ocean-science-related government programs. In 2016, the Chinese government consolidated a number of science and technology programs, including the 863 project, into the National Key Research and Development Program of China. The program lists oceanography, marine resource development, and deep-sea equipment as priority projects.

Ocean science was featured prominently in the 14th Five-Year Plan and likely will also be a top priority in the forthcoming 15th Five-Year Plan. In the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025), ocean science was prioritized through initiatives to build a maritime power by advancing marine technology innovation, deep-sea exploration, and sustainable ocean resource development. In the Fourth Plenary Session communiqué (October 2025), which lays the groundwork for the forthcoming 15th Five-Year Plan (2026–2030), the Party already underscores the importance of ocean science and marine governance, calling to “enhance the development, utilization, and protection of the ocean” (“加强海洋开发利用保护”).

China’s Deep-Sea Science Lab Megaproject

One of China’s most ambitious maritime efforts is a major national project to construct the world’s first manned seafloor laboratory to add to its web of marine research facilities. The new “Cold Seep Ecosystem Research Facility,” which has been under construction since February and is scheduled for operation by 2030, is designed to support a crew of up to six members operating at a depth of 2,000 meters for a maximum of thirty days. It will be the first manned laboratory at that depth globally. Additionally, it will serve as the launch base for AUVs and remote-operated vehicles (ROVs).

Cold seep ecosystems consist of organisms thriving without sunlight by feeding on gases like methane and hydrogen sulfide seeping from the seafloor. The South China Sea Institute of Oceanology, a branch of the CAS, designed the facility to study “the origin of life in deep-sea extreme environments” and explore ocean resources such as combustible ice, which can be found beneath the seafloor and contains methane.

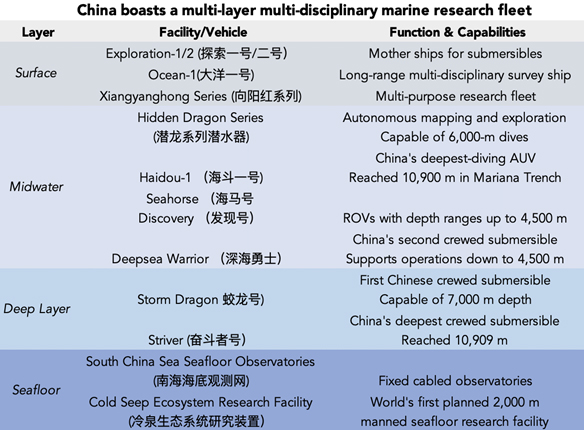

Research Vessels and Undersea Robotics Are a Top Priority

Featured prominently amongst Chinese ocean science efforts is a growing world-class fleet of undersea research submarines and surface exploration and oceanography vessels. The Ministry of Science and Technology subsequently launched a “priority special project” (重点专项) to fund the development of “deep-sea key technologies and equipment.” Its recent grant application guidelines called for projects developing technology, material, and components supporting full-ocean depth submersibles—up to 11,000 meters.

The central government has also launched a series of centrally-funded initiatives to invest in homegrown tech with the objective of establishing an indigenous and globally competitive deep-sea equipment supply chain. China State Shipbuilding Corporation and China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation, both state-owned, have developed a series of manned and unmanned submersibles and ocean gliders in collaboration with research labs.

Notably, manned submersible Striver (奋斗者) reached so-called full-ocean depth by diving 10,909 meters in the Challenger Deep located at the bottom of the Mariana Trench in 2020. Limiting Factor, American-built and operated, still holds the world record for manned vehicle dive at 10,927 meters, achieved in 2019. The vehicle was then piloted by retired American naval officer and private-equity investor Victor Vescovo and owned by his organization Caladan Oceanic (it has since been sold to Inkfish, a research company founded by billionaire Gabe Newell).

The U.S. has a decades-long lead over China in undersea research and exploration. As early as 1960, Trieste—a Swiss-designed, Italian-built, and U.S. Navy-operated submersible—reached a depth of 10,916 meters at the bottom of the Challenger Deep.

The United States has a consortium of more than 60 publicly and privately funded research facilities. World-leading institutes such as Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, Scripps Institution of Oceanography of the University of California, and Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute have pioneered technologies including deep-sea cabled observatory, deep-ocean submersibles, marine robotics, and underwater drones. They operate a global network of cutting-edge ocean monitoring and survey infrastructure and lead across a wide range of marine science disciplines.

In addition, the United States has a group of private companies developing and commercializing deep-sea tech and equipment. They include Triton Submarines, which designed and built the Limiting Factor, and Ocean Infinity, which operates one of the largest autonomous ocean fleets in the world. China’s deep-sea equipment developers are mainly state-owned shipbuilders and defense suppliers.

Table 2: China's marine research fleet

China is attempting to catch up with the United States in undersea technological development, scientific exploration, and equipment supply chain with focused, sustained, and state-driven efforts supporting an extensive and expanding research fleet carrying out frequent deployments. China completed 246 deep-sea dives last year, more than all other nations combined.

China is also investing heavily in AUVs. China’s Key Technologies R&D Program, also known as the 863 Program—after which 863 International is named—has been funding a number of underwater automation projects, which are typically dual use. During a visit to China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation in 2018, Vice Minister of Industry and Information Technology Xin Guobin instructed the company to “place a high priority on military-civil fusion” in developing intelligent ocean technology.

China’s Haidou-1, a hybrid autonomous and remote-controlled undersea vehicle, reached a full-ocean depth of 10,908 meters in 2021. The United States has not deployed full-ocean depth unmanned submersibles since Nereus, a hybrid built by Woods Hole, was lost in a trench dive in 2014. American research institutes and companies are instead focusing on developing and improving AUVs operating at 6000 meters, at which depth 98 percent of the ocean floor lies.

Competition for Deep Sea Resource Extraction

Competition between the United States and China on undersea mining is also likely to heat up. The Trump administration in April issued an executive order aiming to jump start seabed mining, in large part to offset China’s dominance in critical minerals. A number of organizations, including Canadian firm the Metals Company—known as the TMC—and the China Ocean Association, have conducted sea mining trials but have yet to launch any commercial project. TMC’s U.S. subsidiary submitted an application for deep-sea mining to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration immediately following Trump’s executive order.

The International Seabed Authority, established under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), has issued 31 seabed exploration licenses. Three Chinese companies—China Ocean Mineral Resources Research and Development Association, China Minmetals Corporation, and Beijing Pioneer Hi-Tech Development Corporation—collectively hold five of them, making China the largest license owner of any single sponsor nation. (The U.S. has not ratified the UNCLOS.)

Three Pacific-island states with ISA licenses have partnered with the TMC, but in January this year, Kiribati terminated its contract with the Canadian company and reportedly has been considering a deal with China.

Broader Marine Science Efforts

China’s ocean science ambitions now reach well beyond new laboratories and research vessels. They are anchored in a suite of national R&D and engineering programs (国家重点研发计划与重大工程) that link research, monitoring, and environmental management into a single system. Together, they show how Beijing’s maritime vision extends from the deep ocean to the shoreline—and from scientific discovery to state strategy.

One of the most visible of these initiatives is the Marine Environmental Safety and Island Sustainability Program (海洋环境安全保障与岛礁可持续发展重点专项), jointly managed by the Ministry of Science and Technology and the Ministry of Natural Resources. The program funds projects that blend ecology with security, such as coral-reef restoration, storm-surge forecasting, and autonomous reef monitoring. For example, in 2024, researchers from Nanjing University and the Second Institute of Oceanography began deploying new reef-monitoring and coastal resilience pilots in the Xisha Islands, part of a broader push to protect fragile ecosystems while advancing China’s maritime research footprint

Another major line of effort is the Blue Grain Barn Initiative (蓝色粮仓科技创新重点专项), led by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. It pushes marine science into the bioeconomic realm, connecting ocean research to food security. The initiative integrates genomics, selective breeding, and offshore aquaculture engineering to develop sustainable fisheries and deep-water mariculture systems. Recent initiatives include a Dalian University of Technology–led pilot developing high-quality “marine ranching” systems and ecological safeguards for offshore fisheries.

Supporting this growing infrastructure is the Global Ocean Stereo Observation Network (全球海洋立体观测网), a vast engineering project that forms the backbone of China’s ocean monitoring system. It ties together satellites, radar arrays, buoys, and seafloor observatories to provide continuous, three-dimensional data on temperature, salinity, currents, and ecosystems. In 2024 the launch of the national “Ocean Cloud” marine-big-data service platform gave wide access to real-time data streams—an indicator that the network is transitioning from infrastructure build-out to operational service. These undersea networks also have important military applications, allowing China to track enemy submarines.

Beneath these large-scale programs lies the quieter foundation of basic research funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (国家自然科学基金, NSFC). Within its Department of Earth Sciences (地球科学部), the Marine Science Section (海洋科学处) supports studies on circulation, biogeochemistry, and air-sea interaction. Major NSFC programs—such as the Marine Science Major Program (海洋科学重大项目) and the Ocean Process and Climate Key Program (海洋过程与气候重点项目)—fund collaborative teams examining the western Pacific and China’s marginal seas. Current projects include a 2025 team led by Ocean University of China quantifying how meso-scale eddies enhance CO₂ uptake in the Kuroshio Extension, providing new mechanisms for ocean carbon-sink estimates. Unlike the mission-oriented MOST-led national R&D programs, these NSFC grants focus on fundamental processes and long-term observation, ensuring that China’s push for applied marine technology remains grounded in basic science.

Charting the Next Current

China’s ocean-science enterprise is no longer confined to the laboratory or the ship’s deck—it has become a central pillar of the country’s technological and geopolitical strategy. From coral reefs in the Xisha Islands to aquaculture platforms in the South China Sea and a lattice of sensors stretching across the Pacific, Beijing is building a system that fuses discovery with top-down design. China’s efforts are ecosystems, data, and industry into a single maritime framework that extends China’s reach across the global ocean. In this vast and increasingly contested blue frontier, China’s ambitions are as much about imagination as they are about power—turning Jules Verne’s dream of exploring the deep into a 21st-century state project.

Looking ahead, China’s next phase of ocean science will likely move from institution-building to integration—connecting its expanding fleet, labs, and data systems into a unified “digital ocean” platform. Yet this transition comes with internal challenges: coordinating overlapping ministries and funding streams, managing the tension between scientific openness and strategic secrecy, and ensuring that environmental protection keeps pace with development. As the country seeks to balance rapid expansion with long-term sustainability, its success will depend not only on new technologies but on whether its vast ocean enterprise can operate as a coherent and adaptive system—one capable of exploring the deep without losing sight of the surface.

Jimmy Goodrich is an IGCC senior fellow. The views expressed by the author are his own and do not reflect those of any organization with which he is affiliated.

Thumbnail credit: Jeremy Bishop (Unsplash)

Global Policy At A Glance

Global Policy At A Glance is IGCC’s blog, which brings research from our network of scholars to engaged audiences outside of academia.

Read More