The Accomplishments and Contradictions of China’s Semiconductor Industrial Policy

CHINA FOCUS: China Focus is a column for IGCC’s Global Policy at a Glance which examines China’s rise as an autocratic great power and its implications for U.S. national security, the global economy, and the liberal international order. In this piece, Ming-yen Ho outlines what outsiders misunderstand about Chinese industrial policy.

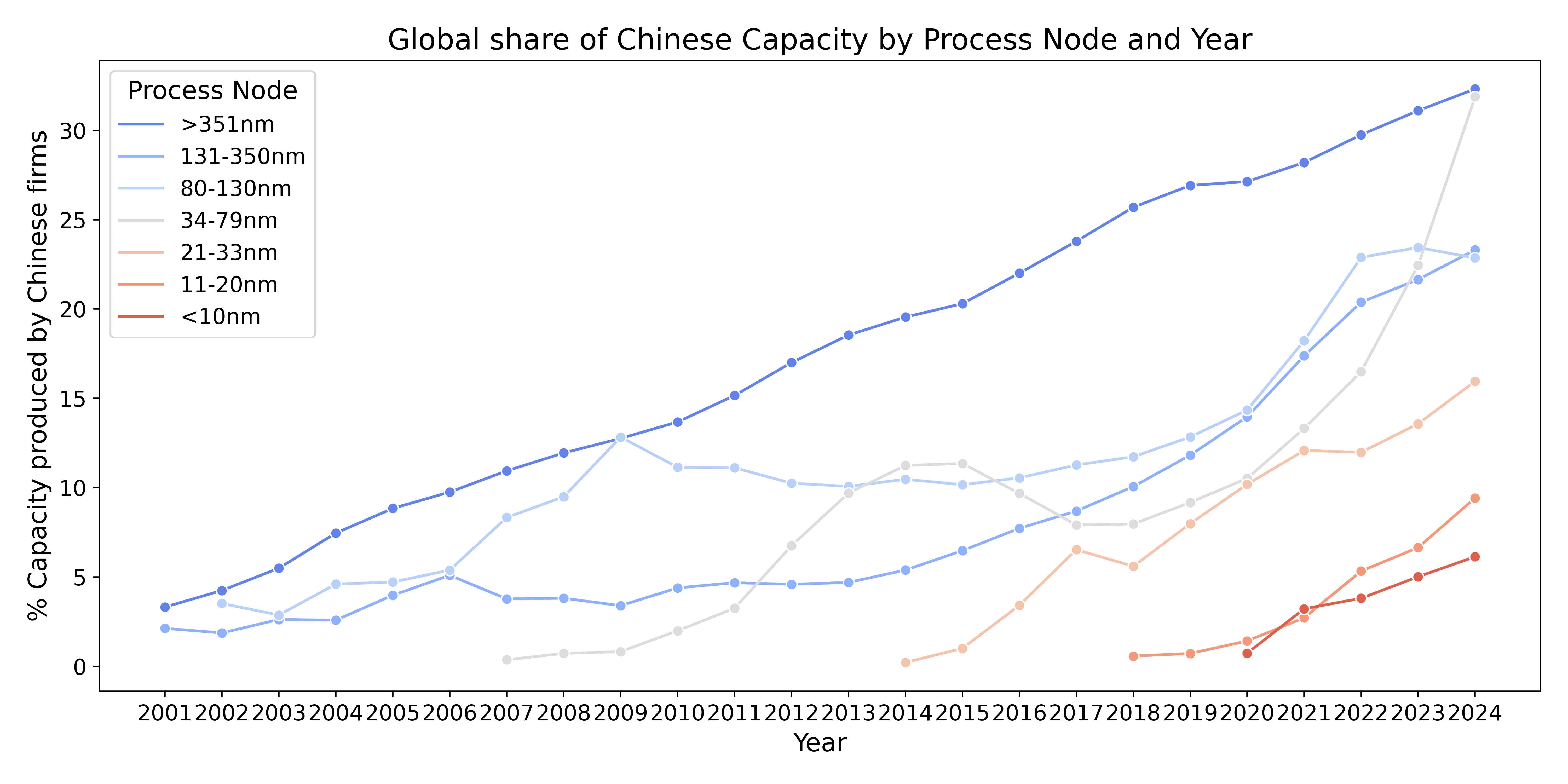

The global semiconductor landscape has undergone a dramatic transformation since the introduction of the Made in China 2025 plan, which made achieving domestic self-sufficiency in semiconductor production a national priority in China. On the technological frontier, Chinese firms continue to advance in memory, compound semiconductor, and logic processes despite increasingly stringent U.S. export controls that deprive China of essential fabrication tools. On mature semiconductors at 28-nanometer processes and above, Chinese firms now comprise a significant portion of global capacity, threatening the profitability of Western and other East Asian competitors with low prices.

Global share of Chinese capacity by process node group (data source: SEMI)

Commentators often attribute the rise of Chinese semiconductors as an outcome of Chinese subsidy programs such as the Big Fund. But there’s far more to the story than throwing money at industry. Rather, the competitive and decentralized nature of Chinese industrial policy has been instrumental to the rise of Chinese semiconductors despite sanctions and trade wars. Despite its successes, China’s semiconductor policy runs the risk of stumbling under its own contradictions.

Chinese semiconductor industrial policy differs from that of its competitors in two respects.

First, local governments at the provincial, municipal, and submunicipal levels have significant discretion and resources to support local firms. Local subsidy programs often explicitly compete with other localities in China. For example, Shenzhen, home to dominant design and consumer end-product firms like Huawei, Tencent, and BYD, is trying to bolster local semiconductor fabrication capabilities, targeting manufacturing strongholds in Beijing and Shanghai.

Second, government support covers the entire supply chain, from upstream design, materials, and equipment, to wafer fabrication and downstream packaging, testing, and assembly. Final electronic products that use semiconductors are also heavily subsidized, including artificial intelligence (AI) servers, smartphones, drones, and electric vehicles (EVs). Globally, this is quite rare—countries typically target support toward segments of the semiconductor value chain where they consider themselves less competitive. The U.S. CHIPS and Science Act, for example, focuses on semiconductor manufacturing with little emphasis on design—where U.S. firms excel—while Taiwan’s Chip-based Industrial Innovation Program targets design and advanced packaging.

This is the essence of China’s industrial policy model, in which subnational officials are evaluated on local economic performance, resulting in decentralized supply chains across the country. In this model, local governments subsidize all sectors with little regard to comparative advantages within the national market.

There are benefits and drawbacks to this model. Intense competition between local-government-supported champions in narrow subsectors of the industry generate inefficiencies as many nationally uncompetitive firms expand production thanks to subsidized costs, which depress domestic and global prices. On the other hand, by targeting the entire semiconductor value chain, buyers downstream enjoy cheaper inputs either through subsidized partners or by exploiting competition between multiple suppliers across the nation. Conversely, downstream subsidies create demand for upstream inputs, justifying suppliers’ capacity expansion. As demand and production surge overtime, manufacturers climb the “learning-by-doing” curve, allowing them to reduce production costs dramatically over time.

With the increase of China’s market shares in compound semiconductor, memory, and mature logic chips, the apparent wastefulness and inefficiencies of its semiconductor industrial policy initially is now being reassessed.

Setting aside a few headline-grabbing failures, local governments have nurtured competitive champions in various subsectors: Hefei’s CXMT is rapidly catching up with leading producers in memory needed for AI applications; Wuhan’s YMTC is now at the global technological frontier in flash memory; and the Shenzhen backed SiCarrier recently announced breakthroughs that make it the most capable Chinese champion in semiconductor manufacturing equipment.

Western commentaries typically gloss over the decentralized nature of this process in favor of analysis that assumes the Chinese state is a unitary actor aiming towards national self-sufficiency. For example, the U.S. government recently initiated trade investigations against China’s nonmarket activity in mature node semiconductors. Reports by the Congressional Research Service and the Bureau of Industry and Security attribute all Chinese firms and their production as “PRC-owned” without distinction between state-supported firms or private firms, let alone distinguishing between local and central champions.

The reality is that Chinese industrial policy is executed by multiple actors with conflicting objectives: the central government wishes to exploit local flexibility while still coordinating national resources to create competitive national champions, whereas local governments are determined to nurture fully self-contained supply chains that are superior to that of other localities.

As a result, support is diffuse, resulting—paradoxically—in both subsidy misallocation and strong market competition forces. Despite inefficiencies, entrepreneurs are incentivized to innovate and cut costs as prices decline, and capable firms rise to gain market share and ultimately become national champions supported by the central government.

These distinguishing features of Chinese industrial policy explain several puzzles regarding the development of the Chinese semiconductor industry: the relentless rise of the country’s manufacturing capacity, the presence of multiple state-supported producers, and the emergence of globally competitive firms supported by local governments despite noteworthy failures early on at the advent of Made in China 2025.

Properly understanding the fundamental decentralization of Chinese industrial policy is necessary for competitor economies to mount a proper response to China’s growing technological and production capabilities. Misattributing Chinese capacity expansion as deliberate intent by Beijing to flood global markets with excess production is misguided, as capacity expansions are driven by numerous competing firms, both national champions and those supported by local governments.

In fact, rhetoric from central government and industry officials has repeatedly warned against overcapacity that could lead to unsustainable price wars. Central government policies have encouraged consolidation and price coordination across semiconductors and other oversupplied advanced manufacturing sectors, including solar panels and EVs.

China’s semiconductor industrial policy has shown great success, but decentralization may not be ideal if the central government wishes to concentrate resources on China’s most productive and competitive firms. But maintaining the benefits of nimble local experimentation and competition while achieving economies of scale remains a conundrum for China—just as emulating or countering China’s semiconductor industrial policy does for its competitors.

Ming-yen Ho is a 2024–25 IGCC dissertation fellow and a PhD candidate in business and public policy at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business.

Thumbnail credit: GetArchive

Global Policy At A Glance

Global Policy At A Glance is IGCC’s blog, which brings research from our network of scholars to engaged audiences outside of academia.

Read More