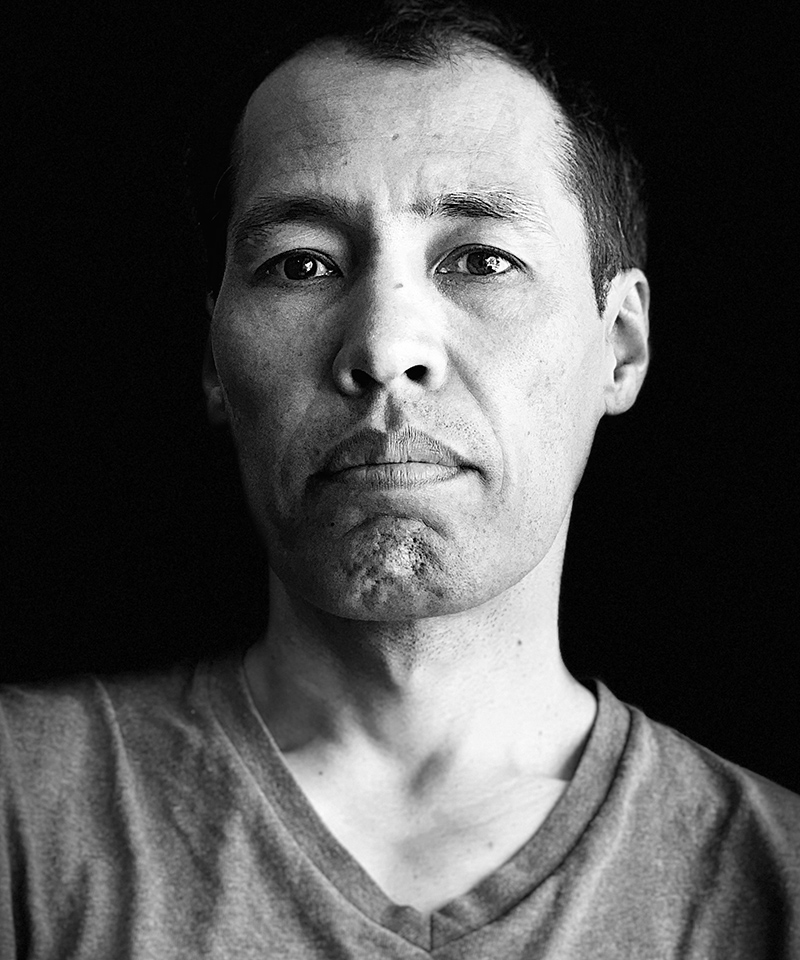

IGCC Dissertation Fellow Spotlight: Nasim Fekrat

In this interview, Paddy Ryan speaks with IGCC dissertation fellow Nasim Fekrat, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Anthropology at UC Irvine, about his journey from being a high-profile blogger in post-Taliban Afghanistan to studying Afghan refugee communities in Washington, D.C. Fekrat opens up about how themes of nation building, ethnic exclusion, and the search for belonging are central to understanding modern-day Afghanistan.

You previously worked as a journalist and achieved quite a bit of fame—in 2009 Foreign Policy magazine called you “Afghanistan’s biggest blogger.” Could you tell us a bit about your background and how you ended up in the United States?

In the early days of the post-Taliban regime, the blogosphere was the dominant platform for sharing ideas and experiences, like social media is today. In 2004, while a freelance journalist, I began blogging in both Farsi and English.

These were two very different audiences. English-language readers wanted to learn about Afghan culture and society, and how Afghans viewed the occupation. Farsi readers were interested in internal ethnic and political dynamics and how people were recovering from the trauma of the first Taliban regime. I quickly gained a large following in the Farsi blogging community. But because access to the Internet was limited in Afghanistan, most of those readers lived abroad.

Afghanistan was changing rapidly, and digital journalism was what it needed. I developed a platform, LOGAF.COM, which enabled Afghans to publish blogs in Farsi and Pashto, the country’s two most common languages.

From 2005-09, I taught several workshops on blogging and digital journalism across Afghanistan, including in Helmand, Afghanistan’s most volatile province, where Taliban insurgents and government and foreign troops fought for control.

On my third day of workshops in Helmand, two Taliban missiles landed behind the building where I was teaching. With my ears still ringing from intermittent explosions, I heard participants shout, “don’t worry teacher, they miss the target, they don’t hit us.” These words are forever seared into my mind.

Blogging and journalism were increasingly difficult as Afghanistan became embroiled in a series of civil wars. I received death threats regularly, and had to sort out which ones were more serious and imminent. I had to be brave. I received freedom of expression awards from Reporters Without Borders and Information Safety and Freedom for blogging and promoting digital journalism across Afghanistan.

My journey to the United States started in Kabul when I befriended a young American journalist, Jeffrey Stern. He helped me get fellowships and admitted into college. In February 2009, I began a media fellowship at Duke University and then at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, where I even met President Bill Clinton.

I graduated from Dickinson College in 2013 with a bachelor’s degree in political science. I then received a master’s degree in religious studies from the University of Georgia in 2018 and a second master’s in anthropology from the University of North Carolina (UNC) Charlotte in 2020. Subsequently, I entered a Ph.D. program in the Department of Anthropology at UC Irvine, where I am now in my fourth year.

From journalism, why did you choose to go into the fields of religious studies and anthropology?

I was fascinated by how religion influences people’s everyday lives. I wanted to understand its influence on immigrant communities and why some immigrants drift away from religion. But I was in a religious studies program where faculty were primarily concerned with medieval literature and religious thinking, something that didn’t interest me.

In my final year, I took an anthropology class which introduced me to major social theories and debates. This shaped my understanding of human behavior. Following my religious studies degree, I completed a master’s thesis in anthropology at UNC Charlotte, where I studied how some immigrants from Afghanistan, particularly those of Hazara ethnicity, show considerable disinterest in religion—many explore alternative faiths or reject religion entirely.

When I began my Ph.D. program at UC Irvine, I wanted to build on my previous research, but the withdrawal of U.S. troops and subsequent collapse of Afghanistan’s republic led to the dislocation of hundreds of thousands of people, particularly the Hazaras, who were vulnerable under the Taliban regime. This made me rethink my research, as I wished to focus more on issues of displacement and trauma rather than religion.

Could you share with us the background of the Hazaras, why you decided to study them, and the methods employed in your work?

Afghanistan is a multiethnic society, and Hazaras are the third largest ethnic group after the Pashtun and Tajiks. Historically, they have been subjected to persecution and genocidal campaigns. They are Shia, while the majority of the country is Sunni. They speak Hazaragi, a subdialect of Farsi and look Asian.

Centuries of intense oppression has led to the forced migration of Hazaras both internally and internationally. Since the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan, nearly 1,000 Hazara households have been violently evicted by their Pashtun neighbors. Destruction, extortion, and looting of Hazara property continues to this day.

Hazaras feel like aliens in their own homeland. This has a deep impact on their identity and sense of belonging.

In the post-Taliban era, hundreds of thousands of Hazara refugees—many highly educated—returned home from neighboring countries. Over two decades of U.S. occupation, Hazara men and women played a major role in nation building and reconstruction. They contributed to important national institutions, especially the security forces, and were prominent in education, sport, and mass media.

My research project is about these 20 years of Hazaras’ struggle for belonging during an era they call “the golden time.” I perform my fieldwork in Washington, DC because it has North America’s largest community of Hazara immigrants. In my interviews, I ask Hazara exiles, how can you belong to a country that constantly rejects you?

In Washington, I recently attended a mela, a popular outdoor gathering in a public park, where over 5,000 Hazaras participated. Their population is growing not only because newcomers are arriving from Afghanistan, but because others are moving from elsewhere in the United States to be close to friends and relatives—and to the center of U.S. politics.

In recent years, D.C. has become home to former politicians, ministers, women rights activists, writers, and journalists of Hazara origin who actively engage with policymakers. This brings them visibility to draw attention to the condition of Hazaras back in Afghanistan.

I study Hazaras’ influence on political engagement back home, their sense of belonging to both Afghanistan and the United States, and how they narrate the story of who they are.

I employ traditional anthropological methods of participant observation, semi-structured interviews, and archival research. I spend significant time with individuals and groups by volunteering in community activities, attending cultural and religious events, and even joining in group hikes, parties, museum tours, playing sports, and meeting in coffee shops.

Another reason for studying the Hazaras in the D.C. area is that I am a Hazara myself. From my fieldwork, I have enjoyed greater access to the community and forged connections with newcomers starting in summer 2019, when I conducted fieldwork for my master’s thesis.

Your dissertation zooms in on this theme of belonging. What makes belonging such a critical factor in understanding modern Afghanistan and the “nation building” goal of the U.S. occupation?

At the heart of nationhood is belonging. But Afghanistan has never been an inclusive nation-state. Previous attempts at nation building failed because they were exclusionary, centering on Pashtun ethnicity and its domination over everyone else.

The past two decades saw an effort to build a nation-state that transcends ethnic and sectarian boundaries in hopes of creating permanent stability.

With the presence of international forces, the Hazaras worked hard to rebuild Afghanistan and demonstrate that they belong. Hazaras were prominent in the Afghan intelligentsia, teaching and producing research at the country’s universities. Major national newspapers and television channels were run by Hazaras. Hazara athletes brought home Afghanistan’s very first Olympic medals, yet were not allowed to fly the Afghan flag because of their ethnicity.

Hazara women were especially prominent in nation-building efforts, contributing Afghanistan’s first female minister, governor, and mayor. Hazara women participated a high rate in the country’s security apparatus. For instance, in a small unit of women that was part of the Afghan Special Security Forces, 90 percent were Hazaras.

The Hazaras contributed mightily to building the Afghan nation. Yet, they are not accepted as “Afghan.” As soon as the United States withdrew, the republic and its institutions melted away. Once again, the Hazara found themselves marginalized.

What does your research have to tell us about political life more broadly?

The story of the Hazara is not unique. Their search for belonging amid dispossession and dislocation is just like that of Indigenous and Black people in the United States, who have shown great resilience in the face of adversity.

Just as we understand how the United States became a nation-state through their stories, we should understand Afghanistan through the experience of the Hazaras. I hope to unsettle the narrative of Pashtun ethnocentric attitudes and tendencies towards understanding Afghanistan and its people. I want to provide a new way of understanding Afghanistan through its peoples’ sense of belonging to the nation.

My research focuses on a little-studied paradox of Afghanistan’s history: that violently excluded minority groups like the Hazaras have played a central role in the nation-building process. It also examines how foreign occupation—meant to bring stability—can actually deepen ethno-sectarian division and further destabilize the country by depending on persecuted minorities, as we have seen in Iraq as well as Afghanistan.

My research aims to enhance our understanding of nationalism by examining how inequities in resources and political power are inextricably connected with divisions in ethnic, sectarian, and gender identities. I also want to examine how forced migration creates diaspora communities that continue to shape the national political landscape of their countries of origin. I hope to provide insights to the public and policymakers about how refugees worldwide negotiate resettlement while recovering from the trauma of displacement.

Nasim Fekrat is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Anthropology at UC Irvine and current dissertation fellow at the UC Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation (IGCC). Paddy Ryan is a senior writer and editor at IGCC.