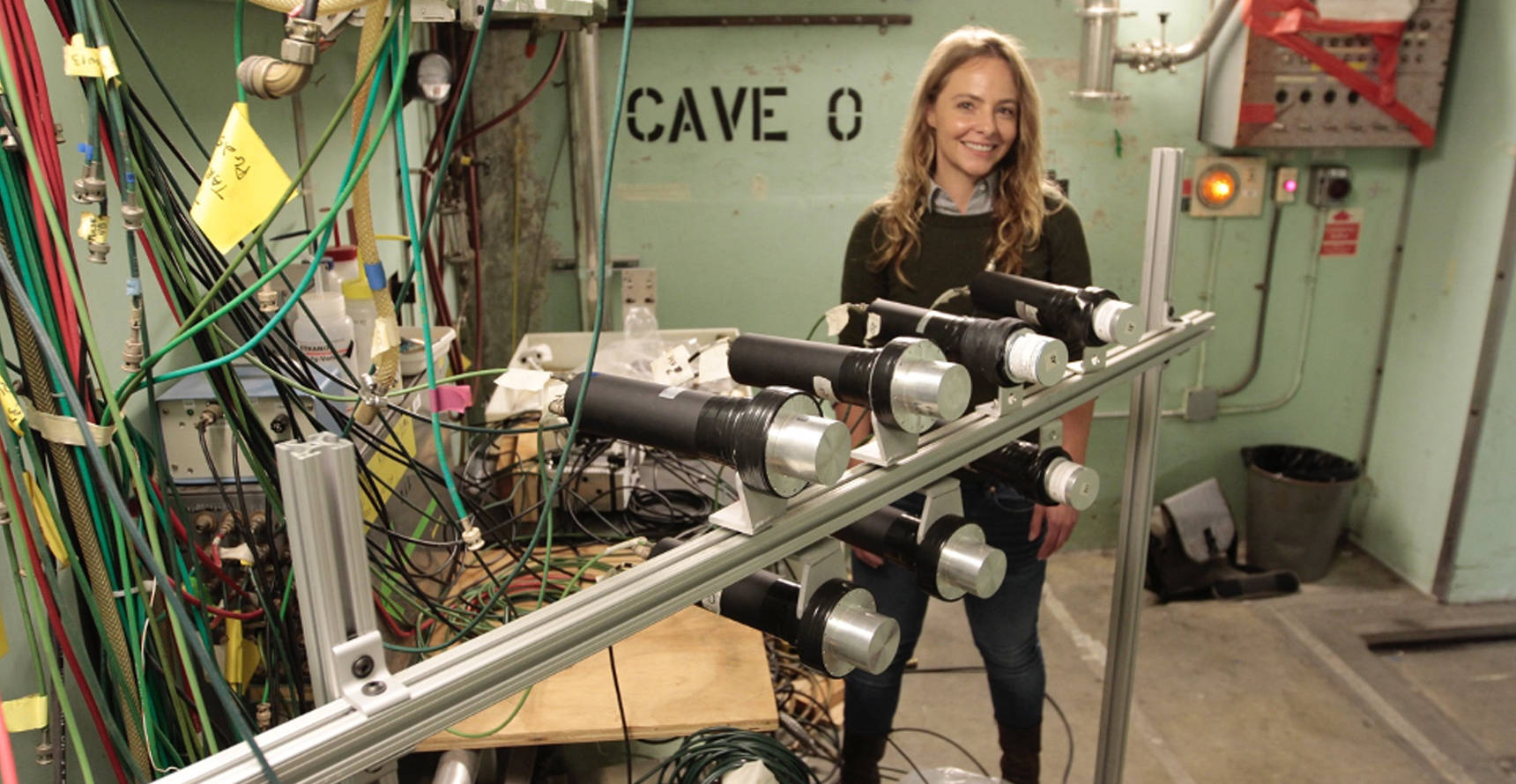

Interview with PPNT director Bethany Goldblum

This month, IGCC will host its 17th annual Public Policy and Nuclear Threats (PPNT) boot camp, our training program on the historical, legal, technical and policy aspects of nuclear weapons. In this interview, PPNT director Bethany Goldblum talks with IGCC associate director Lindsay Shingler about how the program has evolved over the past two decades, and highlights for this year, including speakers like John Scott, Rose Gottemoeller, Laura Rockwood, and Rolf Mowatt-Larssen. Bethany also reflects on whether the world is getting more or less dangerous, and how scientists can participate in ensuring that the technologies they help develop are used for peaceful purposes.

You are a nuclear scientist in the Department of Nuclear Engineering at the University of California, Berkeley. How did you first get interested in the technical sciences?

I’m from a very small town in Louisiana. None of the women in my family worked; it wasn’t really expected that we were going to get an advanced education. So, I had no plans.

I ended up going to a small liberal arts college in Colorado, and started out majoring in math, because I liked the exactness of it. About a year or two in, I started taking chemistry classes, and ended up double majoring in math and chemistry.

You were initially planning on law school after college. Why did plans change?

The summer after graduating, I participated in a six-week nuclear chemistry summer school with the American Chemical Society at San Jose State. It was all day long: it started at eight o’clock in the morning ended at five. There were lectures and labs. It was really intense and really, really cool.

I came out of that with a lot of questions. I was having a lot of joy doing those experiments. Did I really want to go to law school?

I reached out to some of the professors I’d worked with and one of them, Alice Gast, said I could come work with her, but I needed to start the next day. I canceled the enrollment in law school, jumped on a plane, flew out to Delaware, and started making magnetorheological fluids—liquids that harden or change shape when exposed to a magnetic field. Then I flew up to MIT, characterized them, and they flew on a shuttle to the International Space Station. It was crazy.

You went on to pursue your Ph.D. in Nuclear Engineering from the University of California, Berkeley, and it was during that time that you attended IGCC’s first PPNT.

I was interested in weapons design because the physics is really neat. I went through a huge evolution during the PPNT program—it exposed me, not only to all of these different aspects of nuclear science, but also to the policy aspects that I really had not thought about. It was eye-opening.

Just because we work on the technical aspects of a project, it doesn’t mean that’s where our duty ends. We have the responsibility to ensure that the fruits of our technological labor are being used for peaceful purposes. We’re the creators of this work. We can’t expect that some other group of people is going to take the responsibility. Understanding the policy and ethical aspects of the science was something that PPNT gave me.

You’ve served as director of PPNT since 2014. How has the world of nuclear security policy changed over the time that you’ve been involved with the program? And how has the program evolved to reflect changes in the world?

The core PPNT curriculum has not changed. We continue to cover the historical, legal, technical and policy aspects of nuclear weapons issues. But since the program started in 2003, the world has definitely changed, and our program has adapted to continue to cover the most pressing nuclear weapons policy issues of our time. I was a student in the shadow of 9/11. George W. Bush was the president. We were talking about bunker busters, for example, a program at the time to design Earth penetrating nuclear warheads capable of striking targets buried deeply underground. North Korea had just withdrawn from the nonproliferation treaty, so there was a discussion about the potential implications for the sustainability of the nonproliferation treaty.

When I returned to lead the program in 2014, the global nuclear landscape had shifted significantly. Obama was president. Following the 2009 Prague speech, the emphasis was on decreasing U.S. reliance on nuclear weapons. There was serious dialogue about how can we reduce the size of the nuclear arsenal while maintaining our national security objectives? And given that we’re decreasing our reliance on nuclear weapons, how can we continue to transfer knowledge to the next generation as those weapons designers age out? How do you maintain a knowledge base when you’re not allowed to work on these things?

Today, we’ve continued to see a shift. We have a return to great power politics, and we continue to have an increased emphasis on the multipolar nuclear order. We also talk about the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons and the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.

There have been some structural changes to PPNT as well. We’ve significantly increased the fraction of female speakers in the program, which isn’t hard to do because there are so many excellent women in this field. We have also added a simulation exercise at the end of the program, which is the brainchild of Ambassador Linton Brooks.

What are some of the program highlights that you’re most excited about for this year?

The program is going to be held over a week virtually, and it’s very intensive. Last year, we opened PPNT to the public, which was really great, because we were able to reach a broad cross section of technical and policy scholars from around the world. The disadvantage was that the participants weren’t able to deeply engage with the speakers, or each other. This year, we’re going back to having a select cohort of participants. We’re going to try to bring as much of the traditional aspects of the PPNT program into the online environment. We’ve crafted sessions where the balance of time is similar to what we would do in the traditional setting to allow participants the chance to generate dialogue and have professional development opportunities with the speakers.

In terms of content, we have so many excellent speakers. John Scott will be back again—he’s a weapons designer from Los Alamos. Rose Gottemoeller, who was the former undersecretary of state for arms control, is joining as well. She was the former deputy secretary general of NATO and the lead negotiator of the New START treaty. You can’t introduce her without talking for five minutes because she’s just that fantastic. Laura Rockwood, who was head legal counsel at the International Atomic Energy Agency for decades, will be here. Rolf Mowatt-Larssen, who was former CIA and went on to be the head of intelligence and counterintelligence at the Department of Energy, is also joining. He’s at Harvard now. Last time we were in person, someone leaned over and said, “This guy is straight out of a Tom Clancy novel.”

It’s really extraordinary for students to get to be exposed to folks like this.

It is. It’s not like learning about the issues from reading a textbook. What you’re hearing is the on-the-ground experience of policymakers, lead negotiators, and scientists.

You said earlier that scientists have a responsibility to participate in ensuring that the technologies they help develop are used for peaceful purposes. What have you learned about how to do that? How easy or hard is it to strike that balance?

It can feel insurmountable for technical scientists, especially. Policy folks and scientists speak different languages. Literally, the words that scientists use sometimes mean different things to policy people.

We also think about things differently. In science, we try to conclude. We draw boundaries around a problem, and then we make assumptions so that we can try to reach a conclusion. In the policy realm, the focus isn’t on concluding, because there isn’t necessarily a right answer. What they’re going to do is make the best possible decision that they can with the information they have, and the limited amount of time that they have. Understanding the differences between these communities, which comes from interacting—having shared experiences with people across disciplines—is a good first step.

Scientists often feel like—“Hey, I’m not a policy scholar. That’s not for me.” But I think it’s important to realize that this really is a part of your work scope. Policy people want a technical voice in the room. It’s by working together that we can really help make advances.

Do you think the world is getting more or less dangerous in terms of nuclear weapons?

I think the threats are evolving. We need to ensure that our ability to respond to the threats or our conception of the threats continues to evolve as the threat space changes. The total global number of nuclear warheads has significantly decreased since its peak in the mid-1980s, when there were about 60,000 warheads. Now there are around 10,000, globally. From that perspective, if you’re just counting warheads, the risk has decreased. But the total number of nuclear armed countries has continued to increase and the nuclear terrorist threat has become more salient. Our ability to understand and respond to national security threats needs to change as the nuclear order changes.